Thinking through the unthinkable.

I still remember the first time I saw Barb. She was pushing her six-month old daughter in a stroller down the dock at the family cabin next door. We met eventually and so began a friendship that continues to this day.

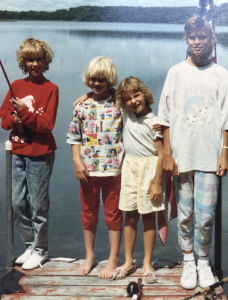

We have shared all sorts of things together, both at our lake cabins and our homes in Nebraska. Summers at the cabins and photos at the end of the dock chronicled the growing up of our daughters. Our lives were intertwined yet separate. My marriage lasted; Barb had several. I stayed in Nebraska; Barb moved to Minnesota and became a real estate agent. Whatever we did and where ever we went, we always shared the time at “the cabin.”

Then came the fateful day when life changed forever. Barb’s daughter Emily was returning from her teaching job in Turkey. Daughter Amy was preparing a welcome home dinner, and Barb was running an errand on Amy’s moped. No one knows for sure what happened. Maybe she skidded on some loose gravel. But helmet-less, she hit a curb with awful results: a traumatic brain energy that left her near death.

Now three years later, the two daughters are their mother’s fulltime caregivers. They share the care, each having Barb in their respective homes for two week periods.

I went to one of the daughter’s homes recently to sit with Barb for a few hours. I’d been spending some time at the lake, the very location where our friendship began. I was pleased the daughters gave me the opportunity to be with Barb. It also gave them a few hours to go together for a spa date. We relished the opportunity — them to have some “me” time, and me to spend some time with my longtime friend.

After the girls left, I sat next to Barb for the next hour as she napped (which she does a lot). The TBI has left her blind and needing help with most basic functions. In that quiet first hour, I admit I wept. I cried for Barb, no longer the vibrant person she once was. Selfishly for myself, for the loss of the kind of friendship Barb and I once had. And certainly for her daughters who have virtually changed their futures in assuming total care of their mother.

Caregivers deserve a special spot in heaven, be they family members or paid staff. Their task at times can be overwhelming. In Barb’s case, she can respond, understand, feed herself but still needs help with all daily functions like bathing, toileting, getting dressed. Occasionally, as in about once or twice a month, the girls have a respite caregiver come in for a 24-hour period. Otherwise, it’s their responsibility. They are fortunate that their “day’ jobs are connected to the family business so they have a certain amount of flexibility. But still, their lives have been indelibly changed.

Barb and I are the same age, 72. Aside from her disability, she is in pretty good health. She recently had hip replacement surgery, came through a bout with COVID and had dental surgery. Conceivably, we both could live for many more years. Barb’s daughters join the ranks of many families who are caring for loved ones in their homes. Like Ann who works full time and comes home to care for her husband, disabled from a brain aneursym. Or Jeanie who cares full time for her 38 year old son who also had a TBI from a car accident. Just like Amy and Emily, they accepted the responsibility and let go of whatever they thought their future looked like.

When the girls returned home I gave them heartfelt hugs and told them their mother would be proud of them. They gave me smiles but with a nod of acceptance that this is their choice and they’re committed to it. Still, I wonder how Barb would feel. I doubt she would have wanted them to put their lives on hold, rather preferring institutional living. I’ve even told my two daughters that’s what I’d prefer. Still, I suspect they’d push to do the same as Amy and Emily.

All this gives me pause to reflect. According to an AARP study, nearly 70% of Americans who reach 65 will someday require help from others to get through the day. On average women will need help for 3.7 years and men for 2.2 years. For Barb, probably a lot longer. The unthinkable is hard to think about, but we must. And we must have the conversation to plan for it.

I guess that’s where we start. The conversation, first closest to home between Mike and I. Then with our daughters. They need to know our wishes, our preferences. These are difficult conversations even under the best of circumstances. Compound that with navigating the “system” which can be complicated and overwhelming. We have durable powers of attorney, one daughter responsible for finances, the other for the health care. But do we have a “do not resuscitate” order written and signed? I don’t know. I need to check. And speaking of checking, we’re making sure the girls’ signatures are on all our banking accounts, safe deposit box, etc. I was surprised the paper work involved in all of that.

As I ponder all of this, I wonder about the entire system of long term care and caring for family members with disabilities. It’s a little like a puzzle that needs to be put together, and the pieces are many: family and individuals, our culture, our government, our health care institutions and the people that run and staff them. They all play a role; there are options. But I still think we need more and better alternatives.

Cost certainly is a factor. Any way you look at it, this care is expensive, and it should be. A valuable service is provided. Caregivers are valuable; they do hard and tiring work. Yet, oftentimes the care being provided is not commensurate with the pay for those “on the ground.” Not unlike the level of pay for child care providers. In both instances, the service provided doesn’t necessarily equate with the payment given.

Which brings me to consider the role government plays. Of course we don’t want Big Brother calling the shots on our lives and those of our loved ones. But if one of our most valuable resources is human capital, shouldn’t government have a role in supporting it. Yes, we have the social safety net of Medicare but it doesn’t extend to care in nursing homes and probably not respite care either. Medicaid is there for the most needy. But there are tremendous gaps and voids that are left.

There are no easy answers, no quick fixes. Emily and Amy will continue to care for their mother as long as necessary. Numerous other family members will do the same. If we refuse to be satisfied with the status quo, I think we can someday arrive at some additional solutions.

As I ended my stay and said goodbye to Barb, I asked if she needed anything. “Yes,” she said, “I need a kiss.” You’ve got it Barb, and a thousand more for the days ahead.